Allandale is host to a rich history that intersects at key points in Kingsport history throughout the last century. But a lot can happen in that time, so we’ve broken it up into digestible points of interest for you. Explore this list of helpful links at your leisure, and learn how Allandale came to be a key East Tennessee landmark.

Click on any link below to begin your tour through the history of Allandale’s interior furnishings.

Video Tour of Allandale

Tell me more about…

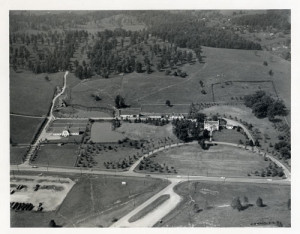

How the grounds were designed

Timashenko, landscape architect to President Dwight Eisenhower, designed and managed the details for the original Allandale grounds. Mr. Wassum [of Marion, Virginia], who also landscaped portions of the White House, was hired to arrange and plant the boxwoods and formal gardens. Allandale Mansion was planned around existing trees [which were by then centuries old], and additional large trees were imported by flat-bed truck and planted throughout the property.

Two large ponds were dug primarily to provide fire protection for the house, but also to beautify the grounds. Original plans also called for a substantial swimming pool complete with Grecian columns and statues.

In recent years, additional bedding plants [as well as dogwoods, magnolias, crepe myrtles, azaleas, boxwoods, and rhododendron] have been added to the back garden, and the Elise Brice Bourne formal rose garden was planted by her husband and friends to commemorate Mrs. Bourne’s dedicated service to the Friends of Allandale.

Most recently, Dr. Harry Coover and his family donated the “Heron Dome” in memory of his deceased wife, Mrs. Muriel Zumbach Coover. The “Dome” features a bronze heron sculpture in a shallow pool, surrounded by benches, landscaping, and lighting to make the structure suitable for evening events [such as weddings, parties, and social gatherings – or simply a quiet spot for reflection and enjoyment of nature’s beauty].

Allandale - private home to public venue

Mr. Brooks was devoted to the interests of Kingsport, and worked in countless ways to make it a better place in which to live. For example, as a predecessor to his gift of Allandale to the city, he donated no less than 100 acres of the property next to his house to the state of Tennessee for a University Center in honor of his first wife in 1962.

Upon his death in 1969, Mr. Brooks left his exquisite home [including many of its furnishings], several outbuildings, and 25 acres [featuring two man-made ponds] to the city of Kingsport. The board of mayor and aldermen were given one year to determine whether or not to accept his gift, which came with two primary provisions: the house must be maintained in the same manner as when its former owners were alive, and it must be devoted to public use.

Had the city turned the gift down, the property would have reverted back to the Brooks’ heirs, and the citizens of Kingsport would have lost one of its greatest public landmarks. In 1970, Kingsport’s Mayor Fred Gillette and the Board of Aldermen made what proved to be a wise decision indeed: to accept the Allandale property, and to agree to abide by the terms of his will. Though it had great potential benefit to the people of Kingsport, Allandale was not opened as we know it today until some 13 years later, thanks in large part to the dedicated efforts of Alderman William R. Garwood.

Mr. Garwood understood the possible service such a property could provide the citizenry, and successfully campaigned his fellow aldermen to finally open Allandale for its intended public use. A director was hired, and volunteers worked tirelessly to ensure that the first floor was redecorated and adequately prepared for its first guests since the City of Kingsport became the owner. In May 1983, an “open house” was hosted by Mayor Norman Spencer and aldermen Richard Watterson, Thomas Todd, Mary Cunningham, Alan Hubbard, George Ainslie, and Bill Garwood to officially mark the commencement of Allandale Mansion’s public life.

Regular maintenance of this home and the adjoining property is no small task, and Kingsport is to be commended for the major outlay of funds required [beyond what Mr. Brooks originally provided] to do so.

However, it was not long before it became evident that additional support would be needed to help keep the property “up-to-snuff,” and in 1989, the “Friends of Allandale” association was established to provide for this need. Since then, the they have made improvements and renovations to the property totaling more than $550,000, and have raised an additional $325,000 through in-kind gifts and services. The Friends have accomplished some remarkable objectives in order to keep the home in a fashion the Brooks family would have approved of.

Mr. Brooks had a charitable penchant for inviting visitors [such as the Boy Scouts, kindergarten classes, and church groups] out to tour his farm. This kind tradition is carried on today in his philanthropic memory as many use Allandale’s facilities for a wide variety of social, civic, and private events.

Main foyer

The grandfather clock at the top of the stairs is over 200 years old, and is of English origin. When wound it still chimes every hour on the hour. Mr. William Barnish, whose name is on the medallion over the dial, was a clockmaker in Rochdale [near the city of Manchester], England. He was born in 1734 and died in 1776, which therefore dates this magnificent timepiece somewhere between 1755 and his death.

The grandfather clock at the top of the stairs is over 200 years old, and is of English origin. When wound it still chimes every hour on the hour. Mr. William Barnish, whose name is on the medallion over the dial, was a clockmaker in Rochdale [near the city of Manchester], England. He was born in 1734 and died in 1776, which therefore dates this magnificent timepiece somewhere between 1755 and his death.

Fixed prominently above the inlaid mahogany console desserte [pronounced “dez-zer-ta”] is a baroque Italian mirror. The design is “garland of peace,” and features a bird at the top.

The deacon’s bench is of Chippendale design.

The rug is Persian, completed around 1920, and of the Meshed [“mah-shed”] design.

As you tour the house, be sure to note the large door locks. Custom-made for Allandale by locksmith L.B. Stacy, each is composed of solid brass and requires a separate key to turn.

Dining room

The large Sheraton dining table [custom-made by Strassel of Louisville, KY] is made of mahogany.

The formal Adam mantle is one of four at Allandale. The Adam brothers [English interior decorators in the 1700s] designed furniture, ceilings, and mantles, which are characterized by straight lines, surface decoration, and medallion details.

The English Heppelwhite sideboard is flat burl and French walnut with an incomplete serpentine design on the ends, and dates from 1790. Wine was stored in the cellarette [French for small cellar] on its right side.

The inlaid-boxwood Dutch china cabinet you see is a very old piece, dating from the 17th century [Elizabeth the First period]. This Dutch style was prominent in the lowlands of Europe and was popularized in England by William of Orange. Interestingly, the shading details on the inlaid flowers were created by applying burning sand to the wood. Inside the cabinet you will find Rosenthal china plates of gold and cobalt blue, and Mr. Brooks’ hobby collection of Claret [“klair-eht”] wine pitchers. The oldest one of these was manufactured in 1902, to celebrate the coronation of King Edward of England.

Two matching Queen Anne tea tables decorate the area before the windows.

The paintings you see in this room are of Lady Lawrence and the Boy in the Velvet Coat. Purchased from The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, they date back to the 1700s.

The chandelier was both designed and made in the former Czechoslovakia [comprised of what is now the Czech Republic and Hungary].

The rug is a Persian Meshed, similar to the one in the Main Foyer.

Allandale Parlor

The lamps [which, interestingly, were French urns at one time], sit atop matching hand-painted Tarbaret [“tar-burr-ay”] side tables decorated with ormulu [“orm-ah-lu”], a word which refers to a manufacturing process of gilding cast metal with gold.

The lamps [which, interestingly, were French urns at one time], sit atop matching hand-painted Tarbaret [“tar-burr-ay”] side tables decorated with ormulu [“orm-ah-lu”], a word which refers to a manufacturing process of gilding cast metal with gold.

The fireplace came from Valley Forge, PA [site of the well-known Revolutionary War winter camp], and bears the date 1835 on the back. The Adam mantle which adorns it is from Gettysburg. The lady in the painting above is unknown, the artwork having been purchased somewhere in Europe by friends of the Brooks.

The two matching Bombay commode tables [of the Louis the 14th period] feature marble tops and black walnut legs with satinwood used on the cabinet. The gilded mirrors hanging above the tables are Italian.

The smoked Venetian-crystal chandelier is also from Europe. It is hand-blown and features bluebell and daffodil flower details.

The painting behind this table displays Marie Antoinette of French historic fame, and was purchased at The Metropolitan Museum of Art [New York, NY], like those in the Dining Room, by Mr. Brooks.

An Indian rug covers the floor. It is a reproduction of a French Savonnaire [“sah-vohn-air”], and is valued at upwards of $17,000.

Living room

This room was the scene of many lively parties and other special events when the Brooks family was in residence here.

The large hand-carved mirror dominating the room is gilt-covered wood. Its massive size and weight require at least three strong men to move it.

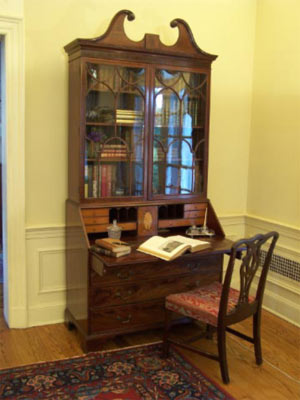

The Sheraton bookcase/secretary [which dates back to about 1785] is of mahogany with applewood marquetry [“mahr-kett-ree”]. Inside are curly-maple drawers and storage alcoves. It features the swan-neck, or “broken arch” pediment design at the very top, which was innovative in that, previous to this time, the arches were designed unbroken. The writing surface is of tooled leather, and the glazed astragal doors protect some of Mr. Brooks’ vast library.

The Sheraton bookcase/secretary [which dates back to about 1785] is of mahogany with applewood marquetry [“mahr-kett-ree”]. Inside are curly-maple drawers and storage alcoves. It features the swan-neck, or “broken arch” pediment design at the very top, which was innovative in that, previous to this time, the arches were designed unbroken. The writing surface is of tooled leather, and the glazed astragal doors protect some of Mr. Brooks’ vast library.

Under each window you will find a pair of “demi-lune” [French for half-moon] tables made of satinwood. They are hand-painted, and feature an inlaid sunburst pattern.

The 1920s-era hand-woven Turkish rug you see covering the floor in this room was specially made to wear well under dancing feet.

A Moran painting is perhaps the most valuable piece in the room. The painter was English and lived from 1829 to 1901. He had three brothers, two of whom were also artists [the other was a photographer]. Moran came to the United States in the mid-1800s to study art, and returned to England for further study in 1862. He came again to American shores ten years later and became a popular painter in Philadelphia and New York City. Moran is especially noted for his paintings which depicted important moments in American history [though his seascapes are also well-known], such as the one you see here.

In this large oil painting, General Chamberlain [wearing gold] introduces Colonel George Washington [in red and blue] to the recently-widowed Martha Dandridge Custis, who later became Washington’s wife…

Living room painting

It is the spring of 1758. Martha has been a widow for six months, and she is visiting her deceased husband’s family, the Chamberlains. It is there that General Richard Chamberlain introduces her to Colonel George Washington. Because she would have been in mourning, Martha was probably actually wearing a grey dress as opposed to the party gown in which she is attired in this painting. It might perhaps even be the gown in which she later married Washington.

It is the spring of 1758. Martha has been a widow for six months, and she is visiting her deceased husband’s family, the Chamberlains. It is there that General Richard Chamberlain introduces her to Colonel George Washington. Because she would have been in mourning, Martha was probably actually wearing a grey dress as opposed to the party gown in which she is attired in this painting. It might perhaps even be the gown in which she later married Washington.

Behind Chamberlain and at his left is his wife and group of ladies who were probably neighbors. Their respective husbands stand nearby in the doorway. Martha’s son, Jackie, is on the stairs with his nurse Oney. At the right, behind Washington, is Richard Nicolas, the attorney who managed Chamberlain’s estate. With him is the Reverend David Mossun, who officiated at Martha’s first wedding and who would also provide this service at her marriage to Washington. Seated in the foreground is Wilhelmina Bird Chamberlain, the Colonel’s mother and the aunt of the deceased Mr. Custis. Beside her is Martha’s daughter, Patsy Custis.

Martha’s servant Culley stands just inside the door at the right, and Mr. Thomas Bishop, Washington’s servant, is seen outside that door. Bishop is holding a chestnut horse which was acquired by Washington at the time of Braddock’s defeat [and it was due to his performance during this battle that Washington was promoted to Colonel].

Master bedroom

The matching double beds found in this room are copies of ones seen by Mrs. Brooks in a “House Beautiful” magazine. They, like the dining room table, were custom-made by the Strassel Company in Louisville. These beds are trimmed with half-canopies and curtains at the sides and back.

The mantle here is the third of the four Adam-design mantles in Allandale and compliments this marble-front fireplace. Before the mantle is a Persian rug of the Sarouk design, made about 1920.

The mirror over the fireplace incorporates gold leaf, and was brought from the Brooks’ former home on Orebank Road in Kingsport.

The Louis the 14th-style dressing table you see is inlaid, and was created around 1820. The Sheraton-design mahogany bench was, like the beds and table, custom-made. Atop this table is a green-and-gold hand-painted mirror, and features Chinoissurie work.

At the back wall is a gentleman’s grooming stand made of mahogany. The mirror is adjustable, and the table part contains small storage drawers that would have held Mr. Brooks’ dressing needs [such as ties, cuff-links, etc].

The cherry drop-leaf table [formerly situated in the small breakfast area adjoining the kitchen] has roped-style legs.

Allandale Library

When the Brooks lived in Allandale, the Library was the room in which they spent the majority of their time. They would frequently sit here to read or listen to music while enjoying a cozy fire in the fireplace.

The large ball-and-clawfoot desk is early Victorian and was Mr. Brooks’ personal desk. It is also a “gentlemen’s desk,” similar to the one in the Parlor, and was therefore designed to be used from both sides. The ornate blue lamp atop this desk was probably originally powered by gas.

The impressive Persian rug seen here is a Mahal design and was manufactured about 1920.

Above the bookcases, you will find several of the trophies Mr. Brooks [with the capable help and guidance of his farm manager, Mr. George Wheeler] won for the black Angus cattle and Tennessee Walking horses raised here.

In 1965, Allandale showed the International Champion female Angus in Chicago, and was the breeder of the Reserve Champion bull. For two years in a row, 1965 and 1966, Ertmire of Haymount, the main Allandale herd sire, was named “Sire of the Year” in the United States. Furthermore, the 1963 International Champion female was sired by an Allandale herd sire, which was bought by a cattle farm [Walbridge Farms] in New Jersey.

Green bedroom (or Groom’s Room)

When the Brooks family lived here, this was one of two guest rooms. Twice damaged by blazes in the kitchen below it, the nature prints on the walls still show signs of these fires [evidenced by burns on the frames and water damage on the pictures themselves].

The twin beds are walnut reproductions. Between them you will find a walnut clover-leaf pedestal table. On it is a hand-knotted lace doily and a delicate glass lamp with tiny hand-painted flowers.

The corner cabinet is undated, but quite old indeed.

Pink bedroom (or Bride’s Room)

This room was also used as a guest room when the Brooks’ were in residence here. It features a bathroom as well as a large walk-in closet, making it an ideal space for last-minute bridal preparations when weddings are held at Allandale.

The four-poster tester bed is a walnut reproduction, and is in fact the one that the Brooks started their house-keeping with.

The chest-of-drawers is walnut with an inlaid design. The “highboy” [tall chest] is mahogany. Both pieces were built here in our region prior to 1820 and feature yellow pine secondary work.

The antique mounting steps were used for climbing into bed when beds had thick feather mattresses. They also contained storage space, which was used for “night-time convenience”.

The small table is made in a clover-leaf design, and it matches the one in the Green Bedroom. The top folds down so that it fits, if need be, into a corner. The room is also complimented by a comfortable wing chair.

To the side of the fireplace is another period piece, a hand-carved walnut “fainting couch” [also known as a chaise lounge]. This name is derived from ante-bellum days when ladies were laced up very tightly into corsets for the purpose of making their waists appear smaller. When said corsets were loosened, the sudden rush of oxygen to their heads would sometimes make these ladies feel faint, and they would recline on these fainting couches until they were able to regain their composure.